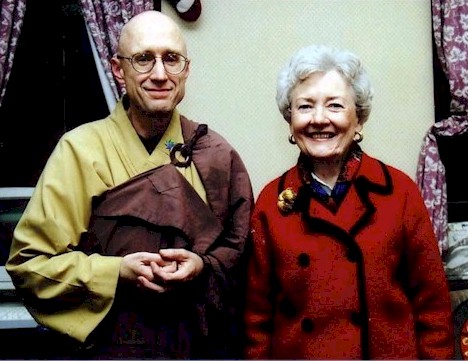

A Bhikshu Mother Heartfelt Words

Mrs. Deborah Metcalf

– Rev. Heng Sure

phot. Dharma Site

My son, Christopher Clowery, became a Buddhist after studying Chinese, first at DeVilbiss High School, then at Oakland University where he earned his Bachelor degree and at the University of California at Berkeley where he was a Danforth Fellow. He translated the Buddhist scripture for his Master thesis at Berkeley and found that it gave him answers to his search for a faith.

At this time, he met a Buddhist Monk, Ven. Master Hsuan Hua, who came to California from Northern China to make Mahayana Buddhism an active religion in this country. He gathered around him graduates from Harvard, Columbia and Berkeley Universities. The Vietnam War was in progress and all these bright men and women were looking for answers to spiritual questions which their religious teachings had not satisfied.

The Abbot and his followers purchased an old factory building in the mission district of San Francisco and established Gold Mountain Monastery – the first of more than twenty monasteries or Way Places, which now flourish from Los Angeles to Calgary, Alberta and in Malaysia, Australia and Taiwan.

I learned more about Buddhism in 1985 when the Venerable Abbot (Venerable Master Hua is referred to as the “abbot” throughout this article) invited me to celebrate my sixty-first birthday with Heng Sure at the City of 10,000 Buddhas.

After Heng Sure’s ordination, he and a fellow monk made an 800 mile “Three Steps, One Bow” pilgrimage up the California coastal highway, from Los Angeles to City of 10,000 Buddhas, north of San Francisco to promote world peace. They made a full prostration to the ground every three steps. This spiritual journey took two years and nine months to complete. For those years and three more, Heng Sure kept a vow of silence, speaking only the Buddhist Dharma, or scripture. I had not received any letters from him for five years because his vow of silence also included correspondence by mail.

With a great deal of anticipation, I flew from Ohio to California for this visit. A lay volunteer at the monastery met me at the San Francisco Airport and drove me to the City of 10,000 Buddhas.

The campus of 75 buildings on a 488-acre area had been a state hospital until Reagan became the governor of California. New laws controlling patients’rights forbade the patients to take care of themselves by growing their own food and maintaining the facility. As a result, they were fastened back in their rooms where they suffered from more mental problems and required more treatment. Additional staff had to be hired to care for everything, and the whole system became such a financial burden to the state that it had to be closed down. The state began a new program of Home Care, which meant the patients were released to their families. Many of them wound up on the streets, creating the enormous problem of homeless people.

When the Buddhists purchased the campus, they established a monastery, a school for children, kindergarten through 12th grade, a home for Senior Citizens, a college and also a translation center. One of the chief activities of the Abbot’s followers in the United States is the translation of the Buddhist sutras, or scriptures. They were last translated from Sanskrit into Chinese in the early centuries of Buddhism. The monks and nuns, some of whom have their doctorates in Sanskrit, have expanded their efforts now into fourteen languages, with many other translation centers.

I am a life-long Methodist, but I was eager to learn all I could about the religion that had captured my son�s interest so completely that he had dedicated his life to it. Heng Sure had been an active Methodist at Epworth too.

As we drove through the impressive pagoda-roofed Mountain-gate of the City of 10,000 Buddhas, I felt as if I was approaching a foreign country; I knew I wouldn’t understand everything that was said or done, and I didn’t know what was expected of me. Up the hill from the gate, I could see a large bronze sculpture of a Buddha under a high roof and beside it, an enormous bronze bell.

I looked forward to seeing again the nuns and monks I had met on my first visit. The nuns are bright, well-educated women who taken vows of celibacy, as the monks have. They wear the brown robes as the monks and their heads are also shaved. It was November and in the cool climate of Northern California, they wore Navy watch caps, but the caps didn’t soften their severe look. At first, I found it a problem that a woman could reject her femininity so completely. Then as I began to know them, I saw past the plainness, to women who had such a mission in life, nothing superficial mattered anymore.

Gwo Wu, an older Vietnamese layperson, who helped me acclimate to the new environment, attended to me as my hostess. She settled me down at one of the cottages, which previously housed the staff and now are used as guest-houses. Each year many Asian visitors come to CTTB for retreats and elder hostellers come there to learn about Buddhism.

Every day at 11 a.m. Gwo Wu took me to the Hall of 10,000 Buddhas where monks gathered on one side, nuns on the other, to recite prayers before their single meal of the day. Guests could go to dining hall for breakfast and dinner if they liked.

My hostess give me a book of the prayers to follow along in phonetic Mandarin Chinese and English. When they changed from deity to another in their worship, the leader beat a gong as well. If I lost my place, someone always gently pointed it out to me. Their awareness of others was touching. I found as mother of the one who had done Three Steps, One Bow or San Bu Yi Bai, I was shown a deference that was totally unexpected.

At the end of the twenty minute service, we filed out in a line following the monks, chanting as we walked to the dining hall down the hill. In the dining hall, the Abbot sat on a raised platform in the center of one wall with about twenty five monks and as many male guests to his left and about fifty nuns and female guests to the right. The Abbot was a stocky man in a gold-colored robe. His face was unlike anyone I had ever met. His expression was one of compassion that was guileless, yet wise. After getting acquainted with him, I had the eerie feeling he knew what I was thinking. Laypeople served the Abbot first, then the monks and male visitors went through a cafeteria line. The nuns and female guests followed.

At the first dinner, I recognized little on the buffet but some bok-choy, rice and tofu prepared to resemble veal, chicken and other meats in several dishes of unfamiliar vegetables. The Buddhist precept that prohibits killing applies to killing animals as well as humans, so the monks and nuns are strict vegetarians. With each dish of Chinese food, my hostess explained the contents, urging me to take some dishes and rejecting others as too strange for my Western tastes. If I indicated I liked something, someone brought me more of it. I tried everything, but I still had some food left on my plate at the end of the meal. I didn’t realize this was a faux pas until I followed my hostess in a line that led to two large dishwashing kettles. We were to dip our plate first in the soapy water, then the clear water. Someone had to clear mine before I could follow the routine. Obviously Buddhists waste no food.

We ate our meal in silence. I discovered it allowed me to concentrate on the food in a way conversation prohibits. Buddhists not only savor each nuance of flavor, they contemplate the work it took to bring the food to the table. They consider whether their conduct merits receiving it, and how greed is a poison to the mind. They think of food as medicine to cure the illness of hunger. They take the food to help them cultivate the Way to benefit all sentient beings.

One day when we had finished the meal, the Abbot began speaking in Mandarin Chinese as one of the nuns translated into English. He announced, “Heng Sure’s Mama is with us to celebrate her birthday” It was the signal for one of the nuns to bring out a cake for us to enjoy. I had not expected the Abbot to observe our Western tradition. It reassured me that he was ready to adopt American customs.

The exchange afterward touched me on a deeper level. One of the American nuns, an Asian guest and I were asked to talk about our sons. In her earlier life, the American nun had a son. The Malaysian mother and I both had sons who had left home to become monks. We were of different ages and had come from different cultures but we had the common bond of a mother’s love for her child and we shared the same sense of loss.

The Malaysian mother also had my concern for our sons being swept up in beliefs we felt might exploit their youthful zeal. I never doubted Heng Sure’s sincerity, but it was the era of cults and both the other mother and I had been skeptical that the Abbot’s motives were altruistic. My stay at the monastery convinced me that my mistrust and doubt about the Dharma Realm Buddhist Association were of my own making, rather than being based on reality. I realized, after getting to know the Abbot, I had misjudged his purpose and Heng Sure’s judgment. I agree with the nun who said, “Now it is time for you to learn from your son.”

When the Abbot asked if I had something to say to the assembly, it was my opportunity to give the monks and nuns a message from their mothers. I said, “While you are enthusiastic and zealous in your pursuit of your new way of life, remember that your parents at home want to share your experience, just as they have shared every other phase of your lives.” I hoped my “write to your mother” message reached their hearts as well as their ears.

After the Abbot’s message for the day, the meal ended and we once again walked in single file to the Buddha Hall to say another group of prayers. We bowed in full prostration, hands and forehead to the floor, many times. I found this was an ideal exercise after eating a large meal.

A Christian missionary asked Master Hsuan Hua to tell him the benefit of bowing. The Abbot explained, “Bowing is like pledging allegiance to the flag. The flag is … a piece of cloth that symbolizes the nation. As a citizen, you demonstrate your respect and acknowledge your citizenship by pledging allegiance.”

“The image of the Buddha on the altar is clearly not a divinity or s Sage. It is a representation, an artistic image … that points back to human who realized the highest wisdom. The Buddha cultivated his nature to an awakened state. The image symbolizes his realization of humanity’s potential and aspiration for the highest goodness and compassion. When you bow, symbolically you honor your own potential for great wisdom. Furthermore, bowing is good exercise. It is not idol worship, which is superstitious and passive. Bowing to the Buddha is a practice of a principle; it is dynamic and active.”

One day the monks arranged for a liberating life ceremony, planned in honor of my visit. Buddhists in San Francisco purchased turtles destined for the city’s restaurants and brought them in crates to the monastery. They were carried into the Buddha Hall and laid in front of the altar where they scrabbled and clawed the wooden crates frantically. When the gong sounded for the prayers and the chanting began, the turtles became very quiet, almost as if they were soothed by the sound. The prayers were for their well-being because the Buddhists believe that by not ending their lives, the turtles can continue to strive toward a higher form, rather than having to start over again in the endless cycle of birth and death.

After the ceremony, my hostess drove me to a nearby lake where the turtles were to be released. I had never held a turtle larger than a silver dollar, and these were the size of dinner plates, but each person there was expected to pick one up and carry it to the water. I chose one that looked docile, but as I took hold of him “midships” his little feet became four rotors that I had to keep from clawing my shirt and slacks. He was as anxious to gain the water as I was to put him down, so it was a quick trip. When I eased him into the water, he disappeared beneath the muddy water immediately and I thought the ceremony was finished.

Gwo Wu said, “Watch. They will thank us.” I thought she was joking, but out in the lake about fifty feet, little heads began to pop up. The turtles turned, looked at us, and disappeared again.

Gwo Wu said, “Keep watching.” In a minute or two, farther out in the lake, turtle heads appeared again, turned, and looked back. I couldn’t believe it.

Gwo Wu said, “They will thank us three times”, and they did.

I can’t explain it; I just know it happened, and it was a very satisfying act of kindness that I enjoy remembering when I see turtle soup on a menu.

During my three-day visit at the monastery, I was surprised to realize I was not as interested in the clothes or jewelry I usually wear. I love color and pattern, but it did not hold the same importance for me in that serene setting. For the first time the brown, plain robes of the Buddhists were logical. Before I returned home, the Abbot and I had a conversation through an interpreter. It gives you one more aspect of his religion.

He told me, “Your God is a jealous god who says, ‘You shall have no other gods before me’ The Buddha says you can believe in your God and Buddha too. Your God is like a parent to you, his child. If you do something bad, he forgives you. Buddha has an adult-to-adult relationship with you. If you do something bad, you are accountable for your actions.”

The many kindnesses of the Buddhists made an impression that has stayed with me. They live their religion in a way that I admire.

Heng Sure has found a way of life that is both productive and rewarding. Last year he received his Doctorate in Buddhism at the University of California. He is now the Director of the Berkeley Buddhist Monastery and he teaches at the Institute for World Religions. He is a director of the United Religions Initiative; he is a published author of books and articles on Buddhism and he has taught courses on Confucian and Buddhist Ethics at the Graduate Theological Union at Berkeley. He lectures in the United States and in Asian countries.

I know he will never marry or give me grandchildren, which is disappointing, but he is influencing many more children than he ever would as a father. It makes him happier than anyone I know, and I can honestly say l am proud that my son is a Buddhist.